Our Quest for AGI Might Lead Us to Rutherford...

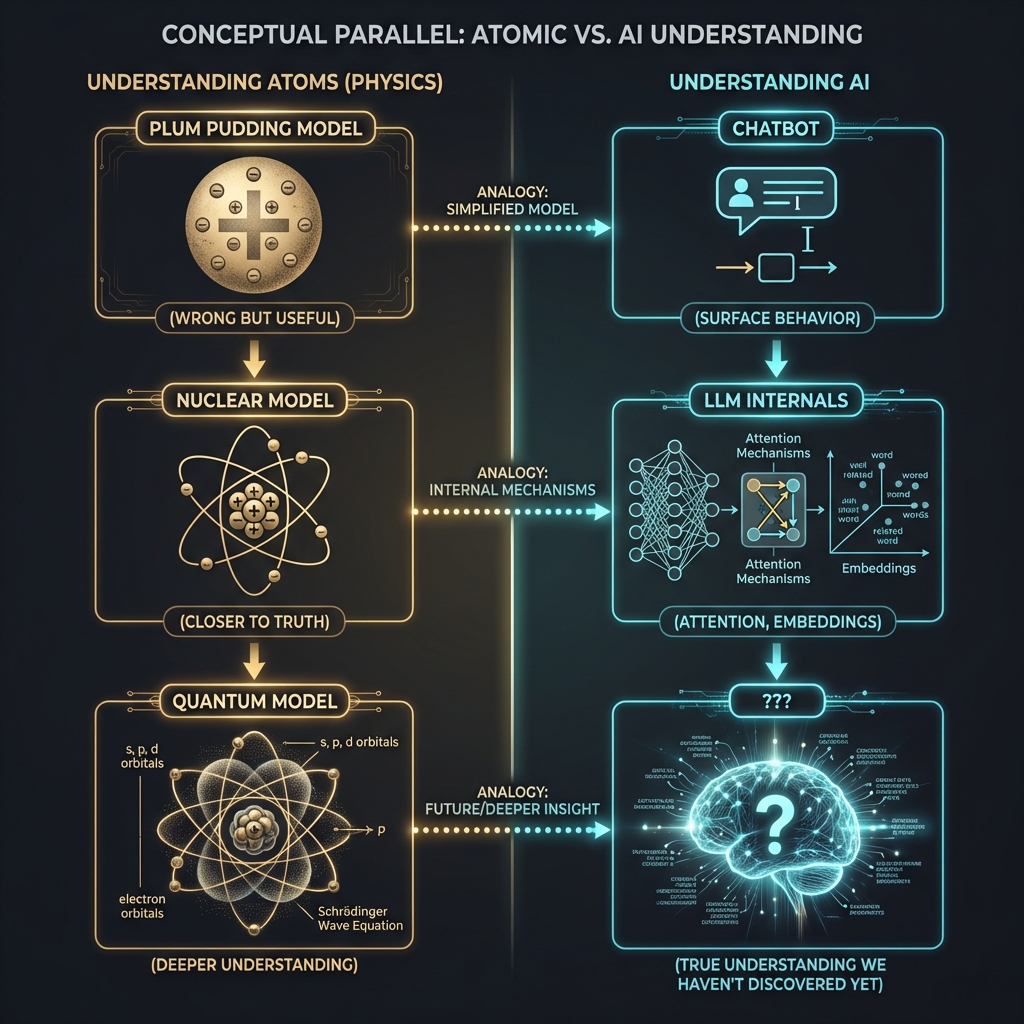

What if understanding artificial intelligence requires the same leap of imagination that understanding the atom once did?

The Most Important Experiment in Physics

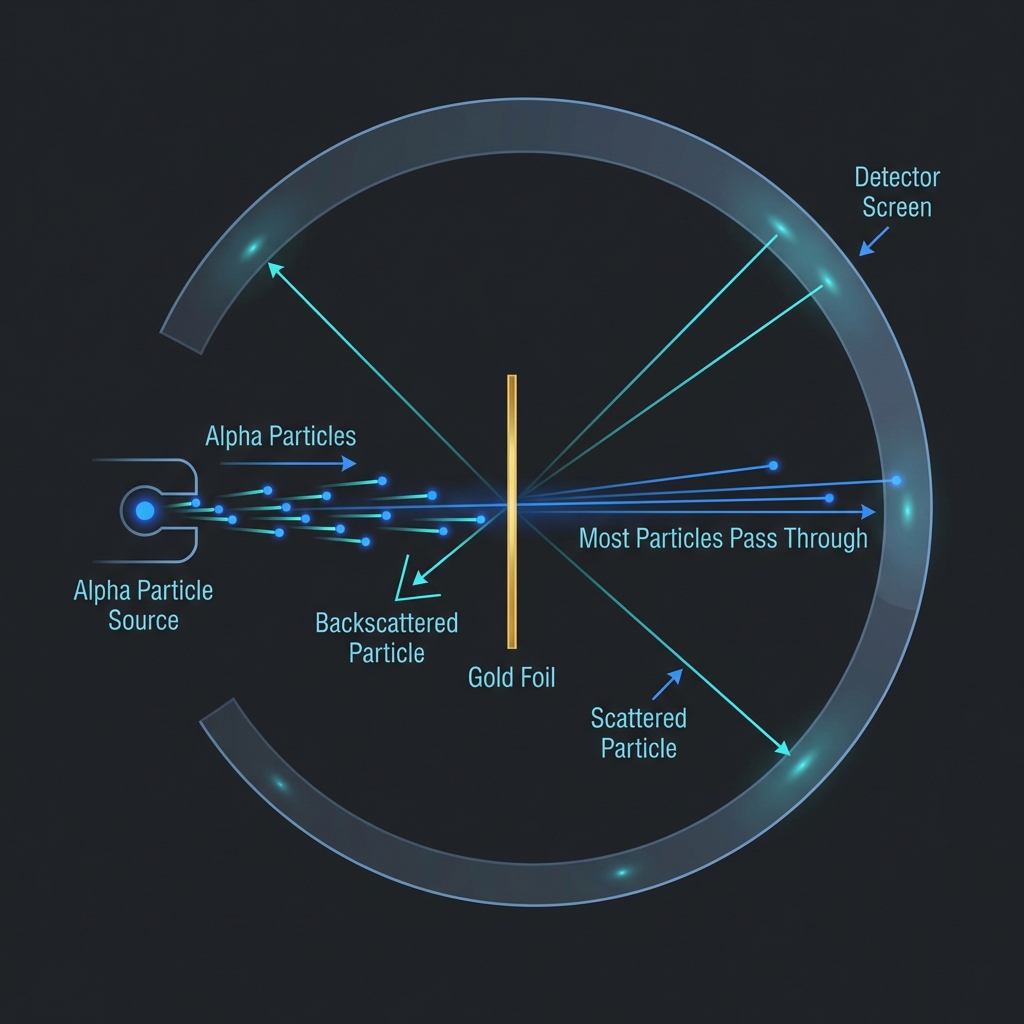

In 1909, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, working under Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester, performed what would become one of the most famous experiments in scientific history.

They fired alpha particles—helium nuclei—at a thin sheet of gold foil and observed what happened.

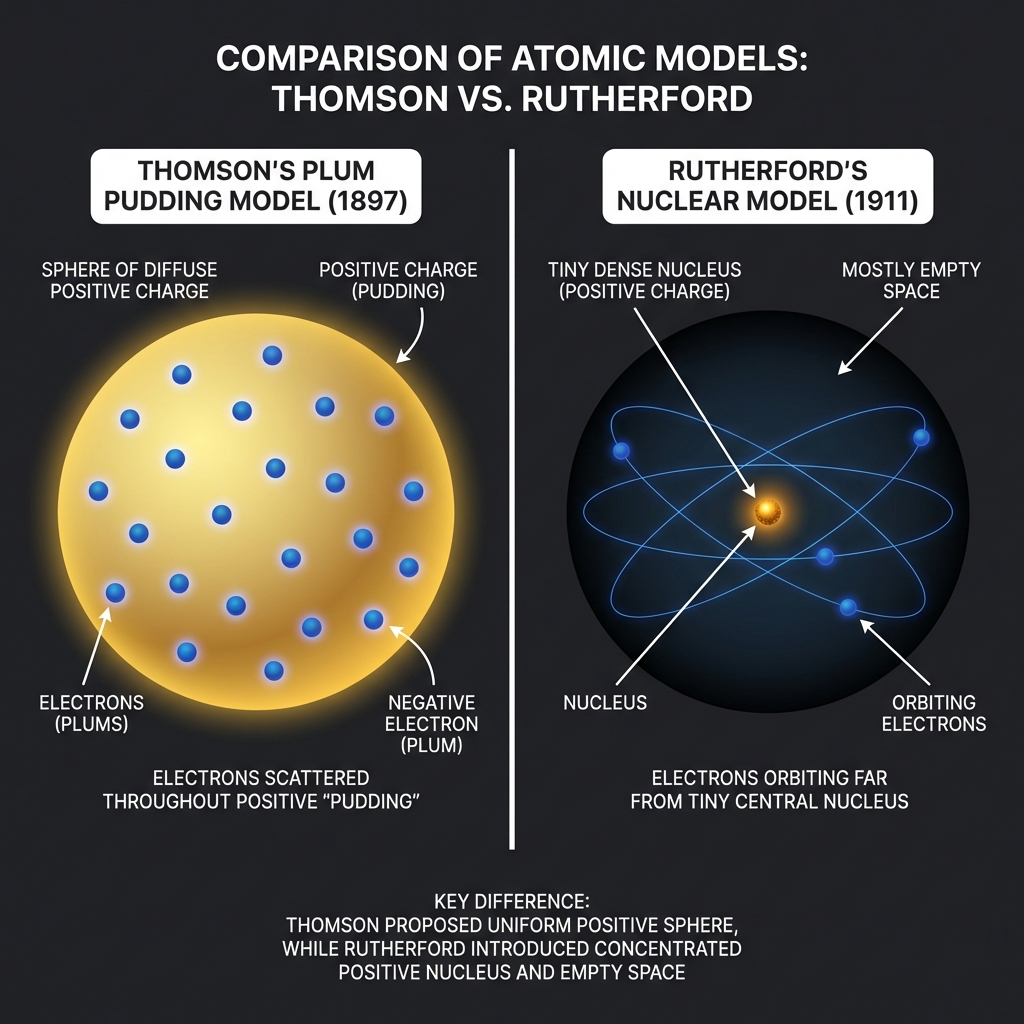

The prevailing model of the atom—J.J. Thomson’s “plum pudding” model—suggested that positive charge was spread throughout the atom like soup, with electrons embedded like plums. Under this model, alpha particles should mostly pass through with minor deflections.

Instead, something strange happened.

Most alpha particles passed straight through, as expected. But a small fraction—about 1 in 8000—bounced back at large angles. Some even came straight back toward the source.

Rutherford’s famous reaction captured the surprise:

“It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

What the Experiment Revealed

The data demanded a new model. If most particles passed through, atoms must be mostly empty space. If some bounced back, there must be something tiny and incredibly dense at the center—a nucleus containing all the positive charge and nearly all the mass.

This was the Rutherford model: a solar system of sorts, with electrons orbiting a sun-like nucleus.

It was beautiful in its simplicity, revolutionary in its implications—and wrong in a crucial way.

Classical electromagnetism predicted that orbiting electrons would continuously radiate energy and spiral into the nucleus within a fraction of a second. The atom should be unstable. Yet here we are.

The Quantum Resolution

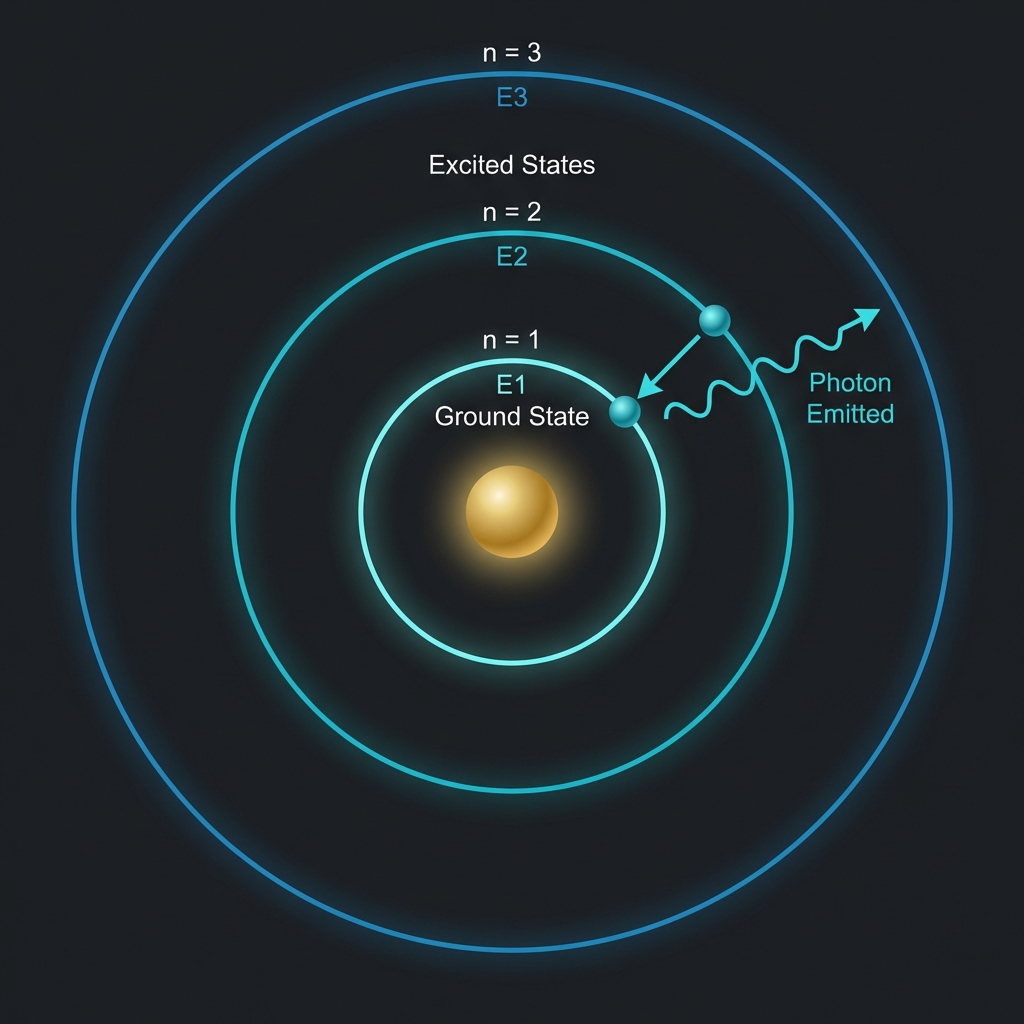

Niels Bohr resolved this in 1913 by introducing quantum theory into the atom.

Electrons, he proposed, don’t orbit arbitrarily close to the nucleus. They exist only in certain discrete energy levels—like rungs on a ladder. An electron can jump between rungs (by absorbing or emitting photons), but it cannot exist in between.

This was the first formulation of quantum mechanics applied to atomic structure, and it worked beautifully. It explained the spectral lines of hydrogen, it predicted new lines that were later discovered, and it opened the door to a completely new understanding of matter.

The key insight: the classical framework was insufficient. You couldn’t understand the atom by thinking of it as a miniature solar system. You needed a fundamentally new set of concepts.

The Parallel to Modern AI

Here’s where this becomes relevant to artificial intelligence.

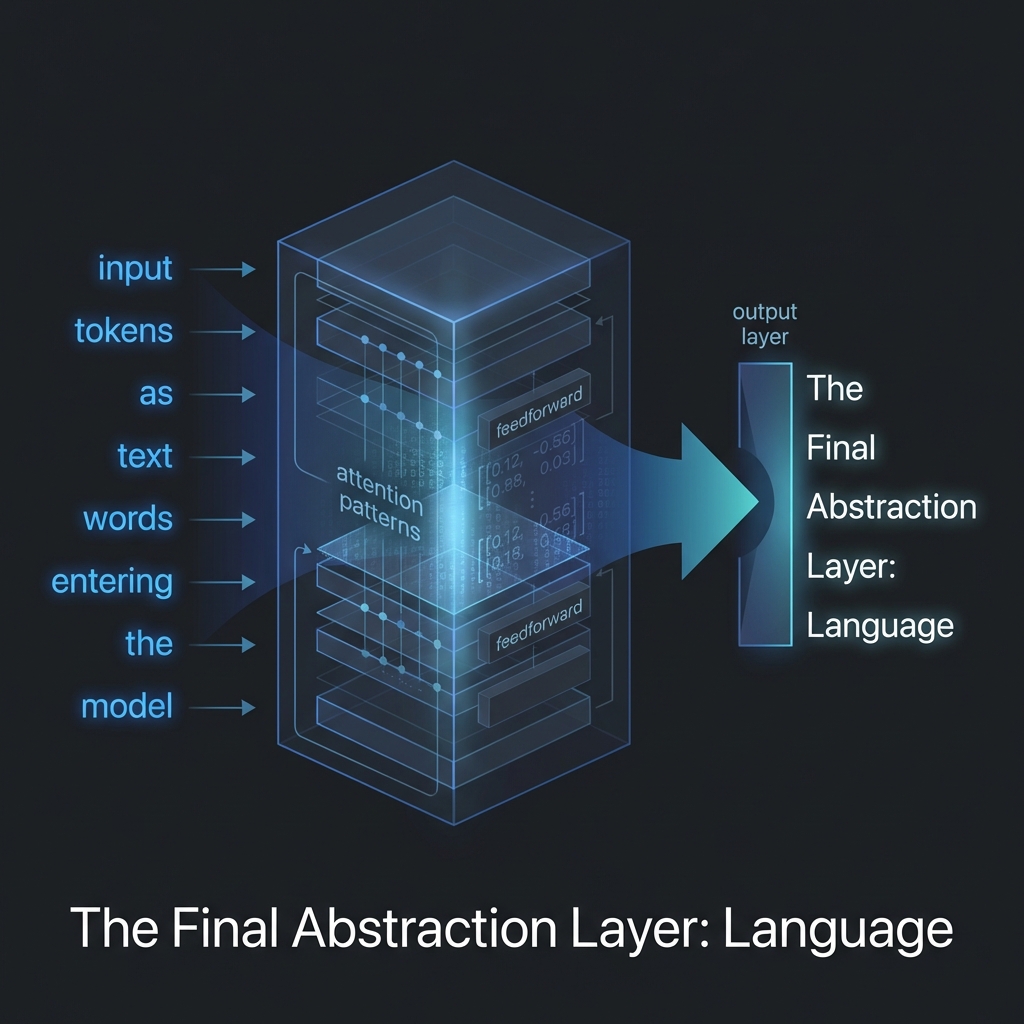

Large Language Models like GPT-4, Claude, and their successors process information through layers of matrix multiplications and non-linearities. They transform tokens into vectors, attention patterns emerge, and somehow—miraculously—understanding appears.

But there’s a curious limitation.

The final abstraction layer is always English.

Or more precisely, the model’s outputs are constrained by the vocabulary it was trained on, the structure of natural language, the biases embedded in human text.

No matter how sophisticated the internal representations, no matter how complex the attention patterns, when the model speaks, it speaks our language. It translates its numerical understanding into words, sentences, paragraphs.

The Rutherford model of the atom—the elegant simplicity at the center—is always filtered through the messy medium of human language.

The Language Barrier

This isn’t just a technical limitation. It’s a fundamental constraint on how we can interact with and understand these systems.

When a model says “I understand,” what does it mean?

The word “understand” is a human construct, loaded with centuries of philosophical meaning. The model has learned to predict that this word should appear in certain contexts. But does it “understand” in any meaningful sense?

Rutherford’s model revealed that atoms weren’t what we thought—they were mostly empty space, with tiny nuclei doing almost all the work.

Perhaps our models are similar: mostly numerical computation, with tiny islands of something that resembles understanding.

The Final Abstraction Layer

The parallel runs deeper than surface-level metaphor.

Rutherford’s experiment forced physicists to accept that reality at the atomic scale was fundamentally different from everyday experience. The atom wasn’t a miniature solar system—it was something stranger, governed by quantum rules.

Similarly, LLMs force us to confront questions about intelligence, understanding, and consciousness.

The final output layer—words in, words out—might be the “classical physics” of cognition, with quantum strangeness happening somewhere in between.

The question isn’t just whether machines can think. It’s whether the very framework of “thinking” as we understand it—the language we use to describe it—is adequate to what these systems actually do.

A Path Forward

Rutherford’s model was wrong, but it was productive wrongness. It pointed toward quantum mechanics, toward a deeper understanding of matter.

Our current language models might similarly be pointing toward something we don’t yet have words for.

The Rutherford model of intelligence—intelligence as language processing, as next-token prediction—might be wrong in important ways. But it might also be leading us toward a deeper understanding of what cognition actually is.

The experiment we need isn’t firing particles at gold foil. It’s figuring out how to probe the internal states of these models, to see what they’re doing when they’re “thinking,” to discover the equivalent of quantum mechanics for artificial minds.

And maybe—just maybe—we’ll find that what we thought was the final abstraction layer is really just the beginning.

Perhaps the most important breakthroughs in AI won’t come from scaling up existing architectures, but from discovering entirely new frameworks for understanding what these systems are actually doing—frameworks that might be as revolutionary as the leap from classical to quantum physics.